The Macroeconomic Background

For more than three decades the American people have been living beyond their means, going deeply into debt at home and abroad to promote a lifestyle that was becoming increasingly unsustainable.

Since the early 1980s, the economy has experienced a long term boom, with average incomes increasing markedly across the entire country and among all income groups but seeds of troubles could be seen.

Here are some main trends of the past few decades:

+ When measured in 2000 prices, the per capita income of Americans has risen from $22,225 in 1980 to $38,000 in 2007, or 70 per cent in real terms;

+ While income distribution patterns became somewhat more skewed, much of this increase in inequality was due to a higher proportion of reduced income retirees in an ageing population and influx of low-income migrants into the country. Despite these trends, levels of real incomes and spending rose across the income spectrum;

+ The boom was encouraged by a rapid rise in international trade, which was both the source of cheap foreign products enhancing the purchasing power of American consumers and a source of cheap foreign saving to finance American domestic investment.

However, as the boom continued, we became increasingly reckless in our spending, with consumption outpacing production, imports racing ahead of exports, and domestic saving increasingly falling behind domestic investment, and our federal budget deficits increasingly financed by debt owed to countries notable only for their hostility to our values and our people.

Large structural deficits emerged:

+ Over the longer-term, the trade deficit has tended to steadily worsen, and in recent years has reached 6 per cent of our GDP;

+ The budget deficit has also tended to worsen and imbalances have regularly exceeded 4 per cent of the GDP.

We have been in a state of domestic overconsumption and underinvestment now for decades. Increasing dangerous and intractable imbalances distorted both the financial and real sectors of the economy, the financial sector through an extraordinary inflow of low-cost foreign saving and the real sector by a corresponding inflow of low-priced imports displacing domestic production and wiping out entire branches of American manufacturing. On the other hand, the inflow of foreign saving boosted the financial sector and investment in housing under government policies intended to promote broad-based home ownership. These developments would not have occurred had policy had been neutral and credit were not cheap.

A Housing Boom Develops and Affects and Infects the Rest of the Economy

Nowhere are the excesses clearer than in housing. Easy credit led to demand pressures on key sectors such as housing and promoted speculation by outsiders who entered the housing market as prices began to rise and increasingly Achurned@ the market toward ever higher levels. Homeownership became a means by which consumers borrowed excessively to sustain their consumption and go further in debt. Cheap credit is also associated with financial innovations, and new mortgage securities were developed to widen the sale of the growing number of mortgages entering the market. The flood of money into mortgage markets also lessened the need to maintain high borrowing standards. Easy credit, lax borrowing standards, over-trading in mortgages and other securities, growing indebtedness all create great risks to the economy.

In particular, over-trading in a market such as housing creates a bubble by stimulating both prices and volumes, and the more people trade, the more the profits accumulate, and the more profits accumulate the more insiders are paid and outsiders are attracted to the market and its offshoots. Everyone=s sense of reason is dulled by constant good news from a rising market in an expanding economy. A state of euphoria develops as people learn of easy riches and massive profits. Many who are attracted to what appear to be easy and permanent gains are foolish and greedy and do not understand that prices in any market cannot keep rising forever at a pace faster than the general price level. In their stupor, they ignore this truth.

Others, not seeking the gains themselves, are drawn in search of work and opportunity in the related industries and activities that support what seems to be a strong and growing sector of the economy. In the case of the housing bubble, real estate firms, building supply centers, home decorating and garden and landscaping services, among many other activities, are stimulated by the increased demand for their services, and they expand along with the housing finance and construction sectors. In the real sector, the interdependencies tighten with the housing core and the fate of firms far removed from housing itself become tied in ways they cannot see and cannot affect. Similarly, in the financial sector, the entire structure of financial assets in the country becomes increasing entangled with increasingly doggy mortgages as these securities are spread far and wide under the assumption that not only are they secure but, more importantly, they represent a liquid asset. The bubble in housing assets encourages a bubble in all capital assets.

Eventually, of course, it must all come to an end. Key people on the inside, seeing the inevitable, take their profits and cash out, all the time pretending optimism and promoting the cruel lie that no problems can be seen. Soon other insiders start for the door, doing their best to be unnoticed as they run to avoid the collapse. Many outsiders sense an end to the party but always assume a gentle decline in prices will not turn into a rout. Then it happens. All at once, prices start to tumble and madness sets in and panic takes over as everyone realizes it has all gone too far. Losses rapidly accumulate, contagion to other financial markets sets in, and credit everywhere dries up.

The expiring financial economy quickly undermines the real economy, and a deep recession sets in.

The Important Role of Government Policy

The boom of the past quarter century was promoted by government policies intended to promote a consumption binge and an unreasonable and unsustainable pace of domestic growth. In the case of housing, affordable housing was seen as a public good because of the stability it encouraged in neighborhoods and the contribution it made to stable family formation. Implementation of this policy focused on favorable tax considerations (most notably, the continuation of the mortgage interest deduction and its use in home-equity loans) and extending more and more mortgages to low and middle-income families with marginal credit histories. Policy also included measures to expand general consumption through higher levels of credit card and other types of consumer debt.

The effort to promote housing began in 1977 with the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA), a Federal law passed to encourage commercial banks and saving and loan associations to channel credit to low- and moderate-income neighborhoods. CRA regulations were substantially revised and strengthened over the years to promote affordable housing in previously under-served neighborhoods. Banks that failed to comply with the policy were threatened with legal action by the Justice Department and suits from community organizations supporting low- and moderate-income groups. Many other government programs fueled the housing boom, including in recent years the American Dream Down Payment Fund and the Home Investment Opportunity Program. All these initiatives led to an substantial increase in the number of bank loans going to low- and moderate income families.

Congress also pushed Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac -- government-sponsored enterprises which own or guarantee almost half of all home loans in the U.S. -- to increase their purchases of sub-prime mortgages going to families with incomes below the median average of incomes. These goals included a target to increase their purchases of mortgages of low and moderate-income borrowers to 50 per cent in 2000 and 52 per cent in 2005. Moreover, government mandates on banks and lending institutions were introduced to override standard criteria used to identify sound borrowers. In doing so, the potential for what would become sour financial assets was created.

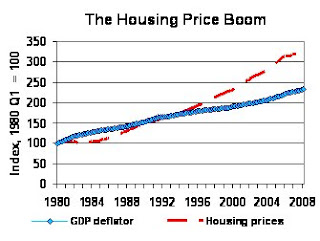

Initially, Fannie and Freddie and the banks opposed the policy measures promoting sub-prime mortgages. But they learned that these mortgages could be profitable as long as housing prices rose and defaults remained low, and their opposition waned. Propped up by the artificial stimulus created by the government=s housing policy, the demand for housing rose and so did the price index for housing relative to the general price index.

Finally, in order to meet affordable housing goals imposed by the Department of Housing and Urban Development, Fannie and Freddie began to purchase sub-prime mortgages for their own account, in addition to the traditional kinds of securities they purchased from mortgage originators such as banks and non-bank mortgage firms. Mortgages backed by and assets from and equity in Fannie and Freddie were purchased by investment banks, and repackaged and sold to other financial institutions all over the world.

In this way, much of the increase in the demand for housing, and hence much of the increase in the price of housing, stemmed from the policies followed by the government and implemented through its quasi-official agencies. The program was successful, perhaps too successful. Homeownership rates rose to record levels B from 64% in 1994 to 69% in 2004 B but the strategy promoted risk and low-quality loans that undermined the housing market. The actions of these agencies, especially their aggressive purchase and sale of sub-prime mortgages, also spread what were to become toxic assets throughout the financial system, including commercial and investment banks, stock brokerage houses, and pension funds.

Novel Securities, an Economic Downturn and Spreading Toxic Securities

Financial booms are often associated with novel ways of providing credit and borrowing money. This boom was one of them. New and poorly understood financial instruments of pre packaged mortgages were created on Wall Street which allowed large blocks of mortgages to be purchased and sold by major financial institutions. Junk bonds, derivatives, and packages of mortgages are examples from the recent rise of financial markets. These and more traditional instruments soon became infected with what were increasingly questionable assets, and these questionable packages were spread far and wide into a financial system here and abroad that did not understand how they worked and what their implications were.

The most toxic of these assets were created early in this decade at a time when a recession began and interest rates were very, very low. Adjustable and teaser rate mortgages built on these low rates were sold to sub prime borrowers that could afford them at the time of the original borrowing but could not afford any significant upward adjustment in the initial terms.

But the Fed did raise rates as the economy recovered from the doldrums of the downturn of the early 2000s and the terms of many of these mortgages were hiked well above what the sub prime borrowers could afford. They began to fall behind in their mortgage payments and default.

Seeing the deteriorating situation, some (by no means all) regulators called for higher credit standards and quick action to stem a potentially disastrous situation. But Congress objected and insisted regulators back off. They did.

The housing market continued to weaken and when the housing price bubble burst in mid-decade, many mortgagees walked away from their houses, and a full scale financial crisis began.

Then the housing crisis spread step by step throughout the country and throughout the entire financial system as packaged mortgages sold far and wide became part of the asset base underneath almost all the country=s financial institutions. They were increasingly recognized as doggy and overpriced. Worse, the complex character of the packages and an inability to establish a price them in an uncertain housing market caused these assets to become untradeable. This problem was compounded by the mark to market rule of the regulators, which forced banks to write down the asset base of the banking system greatly as the prices of these securities fell. Given the highly leveraged nature of the American financial system and the inability to price mortgage-based assets, the entire financial system came to be gridlocked.

The Collapse and Where We Are Now

A financial system is based on trust and confidence. The inability to price assets destroyed trust and confidence. Once trust is removed, technical questions about financial instruments and financial arrangements no longer matter. The entire financial structure collapses in a state of complete confusion and distrust. This is where we are now.

The Fed and the Treasury are now trying to prop up and revive financial markets and rebuild financial intermediaries. Although details of its plans are not known, the Treasury has already announced some of the ideas it hopes to put into place to stem the decent into full financial chaos: The extension of deposit insurance to money market funds, and the full insurance of bank deposits. The new law passed by Congress allows the Treasury Secretary to increase the liquidity of the banking system by purchasing as much as $700 billion in toxic bank assets.

To implement these programs Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson named Neel Kashkari, formerly a colleague of Mr. Paulson at Goldman Sachs and now assistant Treasury secretary for international affairs, as interim assistant secretary for financial stability. Sour assets now held by the banks are of uncertain worth so there is no market for them and hence no price for them. It is reported that Mr. Kashkari intends to use a reverse auction to rebuild bank assets, where banks would offer securities at particular prices and the Treasury would decide whether to buy them or not. Other provisions in the legislation allow for the government to take an equity position in the banks. Of course, these plans may change in light of further developments.

Needless to say, it will take time to put these programs into full effect, even with experienced, if unemployed, investment bankers. These assets to be brought forward for sale by the banks are complex because they include derivatives and securitization. Moreover, it is by no means what is inside some of these packages in terms of the quality of the underlying assets, and therefore it is by no means clear what their price should be. It will take time to set up the institutional mechanisms to carry out the asset purchases and even longer to figure out how they should be priced.

They will not succeed anytime soon. The financial system will have to be rebuilt, and to rebuild it trust and confidence will have to be restored. This will take even more time. In the interim, ad hoc measures will no doubt be introduced to limit the damage.

Looking to the Future

For and foremost in the rebuilding task is restoring macroeconomic balance by matching domestic saving to domestic investment, thereby removing our dependence on foreign sources of saving to finance our national needs. The needed adjustment is large and requires reintroducing domestic economic discipline into a country that has ignored it for decades.

In the first instance, a believable statement of government policy about a future that balances the budget and limits our excessive dependence on foreign sources of oil must be announced. This statement must make clear the approach to be followed in overcoming the crisis, specifically, whether it will stress restraining government spending or focus on raising additional revenue through taxation. And it must be honest about where the burden of the adjustment to a more sustainable economy will be centered, specifically, on those groups or sectors where higher taxes or lower expenditures will fall and the industries that will be most adversely affected and what governments intends to do to mitigate the costs of the adjustment process.

No such statement or suggestion about how to approach the problems before the economy has even been hinted at. To the contrary, both Presidential candidates have avoided saying anything significant about the crisis, even denying it will have much of an impact on present policy intentions.

There is also the problem that we are in the midst of a political campaign and it will be months before whoever is elected assumes office and can set policy with regard to the bailout of the financial sector and the longer term rebuilding of the real economy. Until the policy approach of the new President is known, actions taken by the Treasury will be limited.

Were he to be elected, John McCain would no doubt follow a policy approach that emphasizes reliance on the market mechanism to restore stability and growth. It would in the first instance deal with restoring financial stability but it is increasingly recognized that the country must also eliminate the outsized structural imbalances that now describe the budget and trade deficits. In the long run a market oriented approach would lead to a more efficient outcome and a more vibrant economy than alternative ways of dealing with these problems. But market oriented approaches come with very high short term costs in terms of unemployment and loss of incomes in those areas that suffer from downsizing and a redeployment of their resources. Because of its costs, market oriented adjustment is not popular, and even if elected a President McCain would find considerable opposition to implementing his program.

Were he to be elected, Barack Obama would likely follow a more government oriented approach, in the hope that it can be more rapidly implemented and, with the exception of the financial services sectors, would not entail far reaching and painful adjustments likely to increase unemployment for any sustained period of time. He would no doubt regulate financial service firms more closely than at present and would also be more protective of those affected by change in the economy and attempt to slow down the process of structural adjustment. A President Obama would also be more protective of the environment and be more incline to allow government policy to intrude into the decisions of firms. In the long run, government oriented approaches tend to lead to a more inefficient economy and a slower pace of change but one with a lower degree of inequality and a higher degree of moral hazard. In the short term, government oriented approaches are more popular but the longer they are pursued they tend to generate greater resentments rooted in the inequities of unshared burdens and unfair subsidies to those who have made poor economic decisions and refuse to adjust.

At this time, it is by no means clear who will win the election and the policies they will actually put in place. Until this question is settled, the Treasury and the rest of the country cannot really a program for a recovery and restoration of its economy.

Finally, the economy is going down. Nothing can stop the decline. The question is only how far down and how long the decline. That depends on political leadership that, at the moment, is entirely absent.

No comments:

Post a Comment